The Pursuit of Truth: Eddington, Einstein, and the Eclipse of 1919

June 28th, 2021

51 mins 51 secs

Season 1

Tags

About this Episode

In 1914, most scientists claimed their work knew no borders, but the Great War slammed the door on international scientific cooperation. So when a obscure German physicist named Albert Einstein presented a radical new explanation of gravity, he feared no one outside of Germany would be willing to help confirm his theory. He had no idea that his work would come to the attention of the one man able to make the critical observations and willing to explore German ideas--the pacifist astronomer Arthur Eddington.

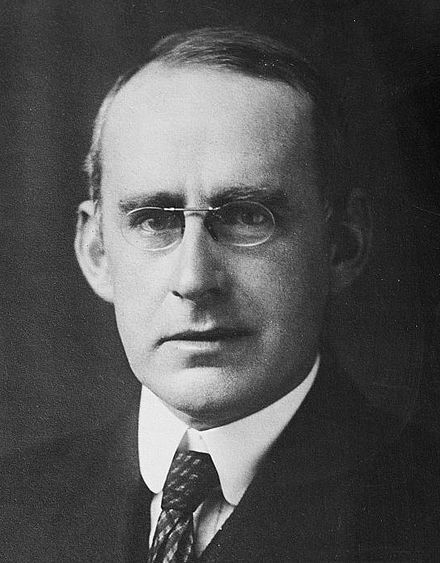

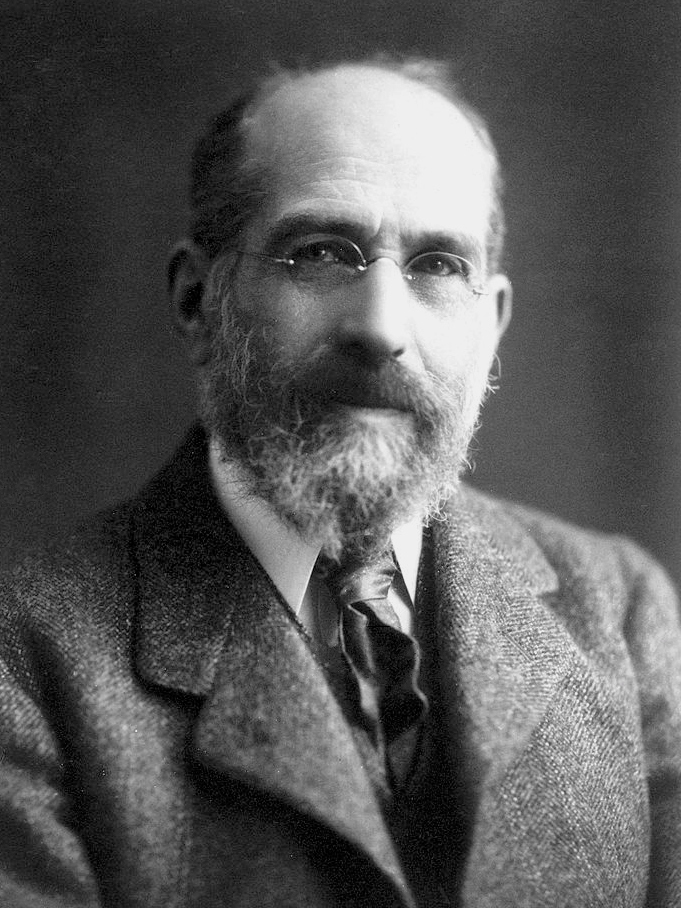

Arthur Stanley Eddington was born in 1882 to a devout Quaker family. He would remain a faithful member of the Society of Friends his entire life and shared their deep conviction in pacifism and opposition to war.

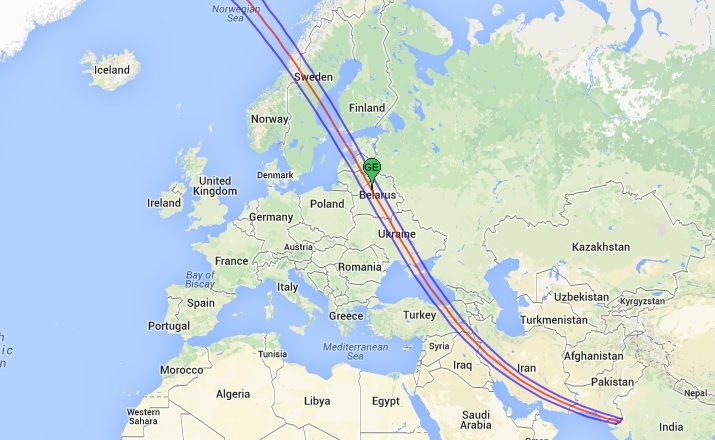

Eddington's first total solar eclipse was in October 1912. This map show the path of totality. Eddington was stationed with several teams from around the world in Passa Quatro, Brazil. Unfortunately, the eclipse was rained out--an all-too-common occurance.

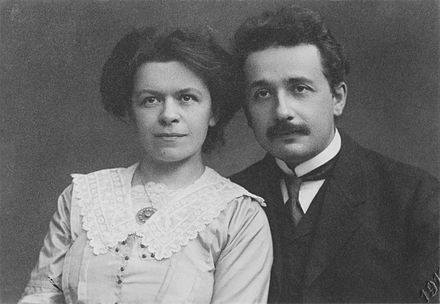

While in Brazil, Eddington was likely told about the work of the still-obscure German physicist Albert Einstein. Einstein, seen here with his first wife Mileva, had already published several groundbreaking papers and had begun his work on general relativity. In 1913, he moved to Berlin to teach at the University of Berlin and become the director of the Kaiser Wilhelm Institute for Physics.

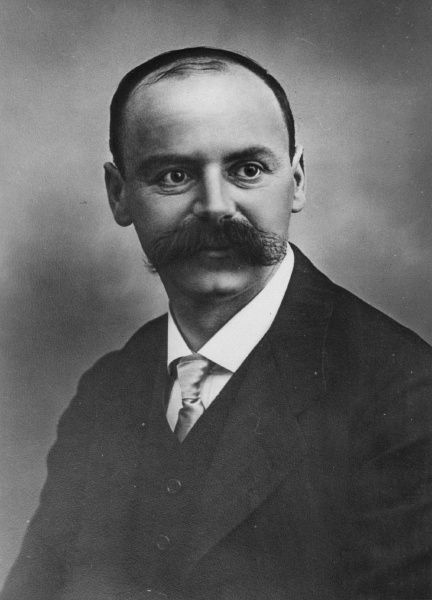

Einstein discussed his Theory of General Relativity with the German astronomer Erwin Freundlich, seen here looking like the villian in an early silent movie. Freundlich passed the ideas on Charles Dillon Perrine, who most likely described them Eddington. Freundlich mounted an expedition to observe the 1914 eclipse in Russia to prove Einstein's predictions on the deflection of starlight.

The 1914 eclipse passed over Sweden and Norway, into Russia, and down through the Ottoman Empire and Persia. Astronomers believed they would have the best conditions in Ukraine and Crimea, and many of them set up there in late summer 1914.

War broke out before the eclipse took place. Freundlich and his German team were detained by Russian officials. British and American teams were able to go on with their work, but again, the eclipse was rained out. The teams then face the difficult task of getting out of war-time Russia. They all had to leave their equipment behind, and getting it back was a lingering headache. The American team didn't receive their telescope and cameras until 1918.

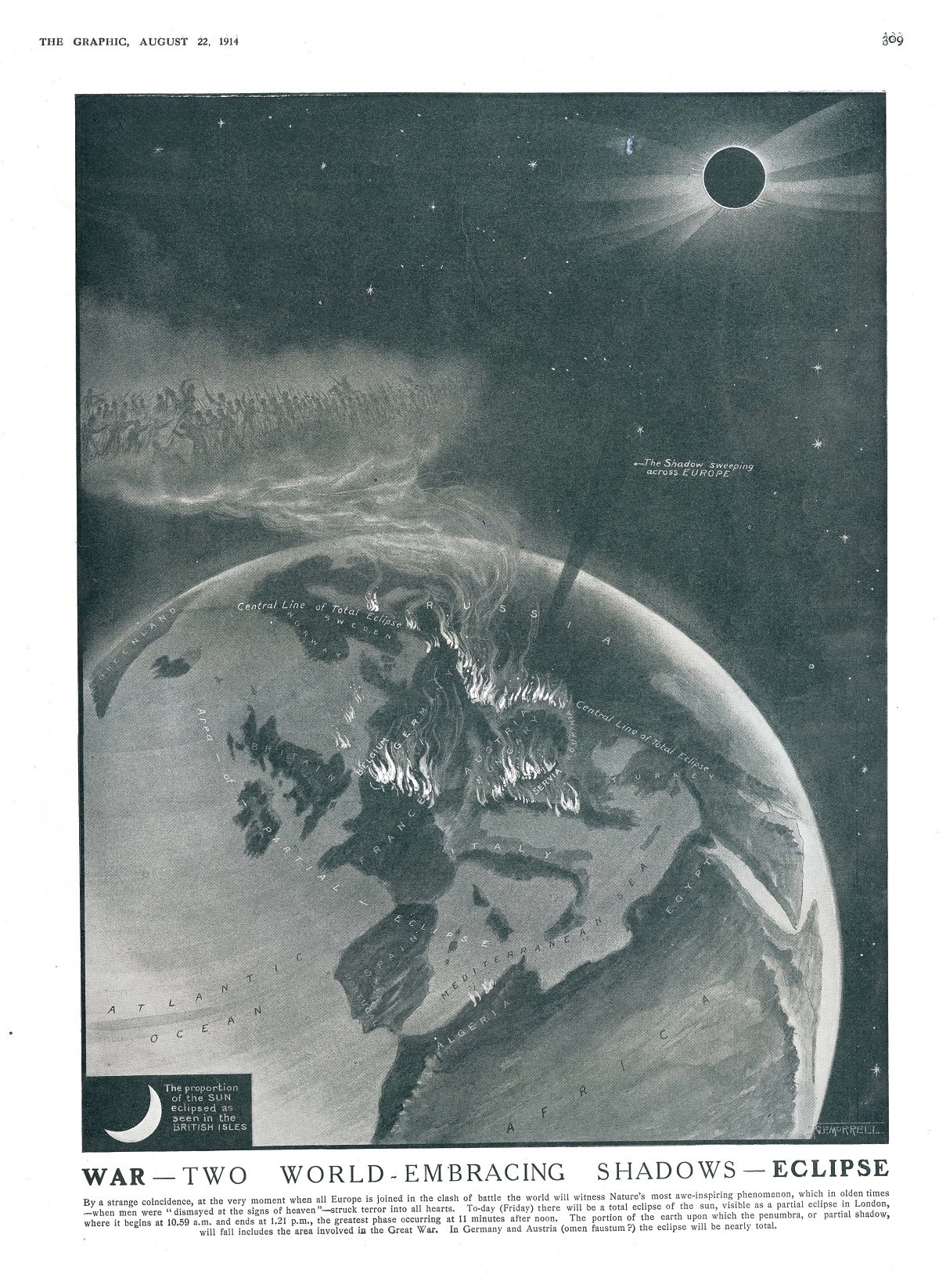

This fascinating graphic from the weekly British illustrated newspaper The Graphic combines a map of the path of totality with a map of the conflict in Belgium and northern France, Serbia, and the Russian border. The graphic ominously describes "The Shadow Sweeping Across Europe."

Allied outrage at German atrocities in Belgium prompted a spirited defense of German actions by scientists, writers, artists and theologians including Fritz Haber. The "Manifesto to the Civilized World," also known as the "Manifesto of the 93," offended Allied scientists and prompted many to call for complete repudiation of German science. Einstein refused to sign the Manifesto.

British scientists relentlessly hounded German-born astronomer Arthur Schuster, despite the fact he had moved to Britain as a teenager. His son served in the British army and was wounded in the Dardanelles.

At the same time, British physicist James Chadwick, who was studying in Germany in 1914, was detained in a former racetrack. He remained in German custody under dire conditions until the Armistice.

Einstein published his complete Theory of Relativity in November 1915. One of the few German scientists who showed any interest was astronomer Karl Schwartzchild. Schwartzchild was serving in the army on the Russian front, where he put his advanced mathematic skills to use calculating artillery trajectories. In his spare time, while under heavy Russian fire, he worked through the math in Einstein's paper. He demonstrated that the math worked beautifully to calculate the movements of planets and stars. He also inadvertently, and without at all realizing it, discovered black holes.

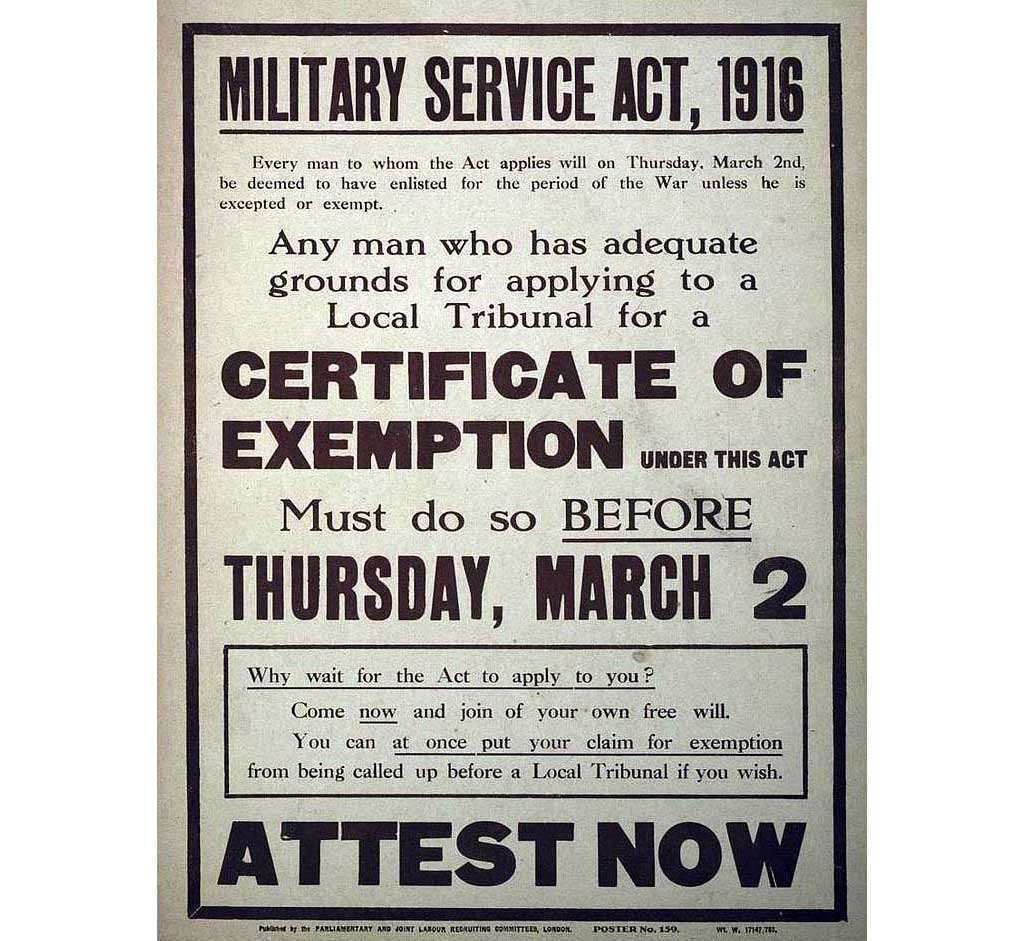

Britain tried to fight the Great War with a volunteer army, but by 1916 it was clear conscription would be necessary. Men could claim exemption for hardship, work of national importance, and conscientious objection. The goverment established tribunals to issue these exemptions but offered no guidance on qualifications.

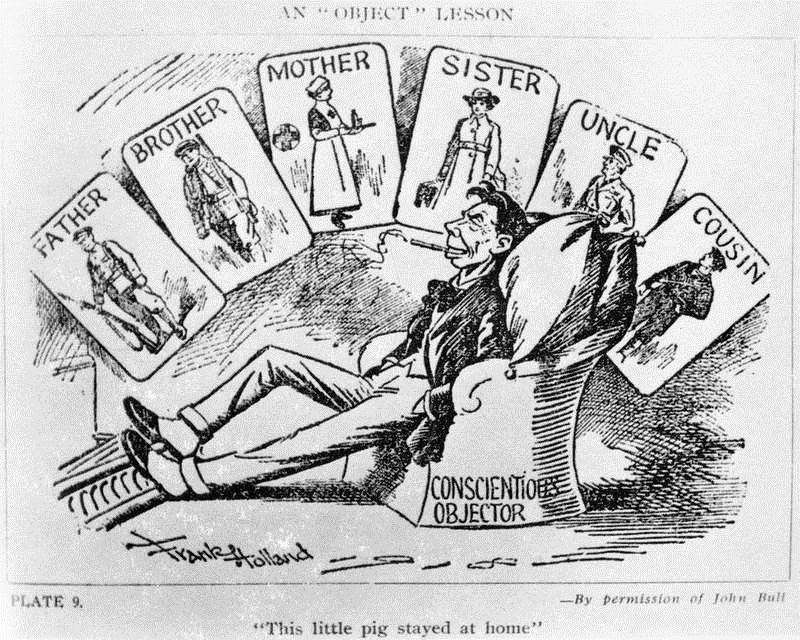

Conscientious objectors were deeply suspect as slackers and cowards. In this editorial cartoon, a lazy conscientious objector lounges before a fire with a cigar ignoring images of his entire family doing war work. It is titled "This little pig stayed home."

Meanwhile, light from the Hyades star cluster continued on its way toward Earth from 153 light years away. (Image copyright Jose Mtanous, from science.nasa.gov.

Support The Year That WasEpisode Links

- "Einstein's War: How Relativity Triumphed Amid the Vicious Nationalism of World War I" by Matthew Stanley: 9781524745424

- "Proving Einstein Right: The Daring Expeditions that Changed How We Look at the Universe" by James Gates and Cathie Pelletier

- History of Quakers | Quakers in Britain

- Remembering the "World War I Eclipse" - Universe Today

- "The big Australian science picnic of 1914" by Rebekah Higgitt | Science | The Guardian

- Oral History Interview with James Chadwick Describing in Internment in Germany, American Institute of Physics

- Simple Relativity - Understanding Einstein's Special Theory of Relativity - YouTube

- Einstein's Theory of Special Relativity | Space.com

- Einstein's Special Theory of Relativity | PBS LearningMedia

- "Black holes on the Russian Front" – A Mind of Many Blog

- First World War Attitudes to Conscientious Objectors | English Heritage