A Gladiator's Gesture: Art after the Great War

September 24th, 2019

42 mins 46 secs

Season 1

Tags

About this Episode

In 1919, two competing art movements went head-to-head in Paris. One was the Return to Order, a movement about purity and harmony. The other was Dada, a movement about chaos and destruction. Their collision would change the trajectory of Western art.

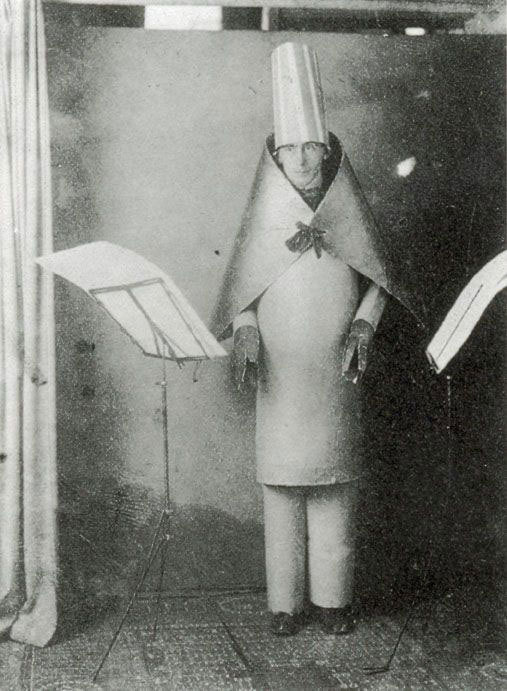

Hugo Ball established the Cabaret Voltaire in Zurich, where Dada came to life in February 1916. In this photo, he's dressed in his "magic bishop" costume. The costume was so stiff and ungainly that Ball had to be carried on and off stage.

You can hear the entire text of Ball's "Karawane" on Youtube. You can also read the text.

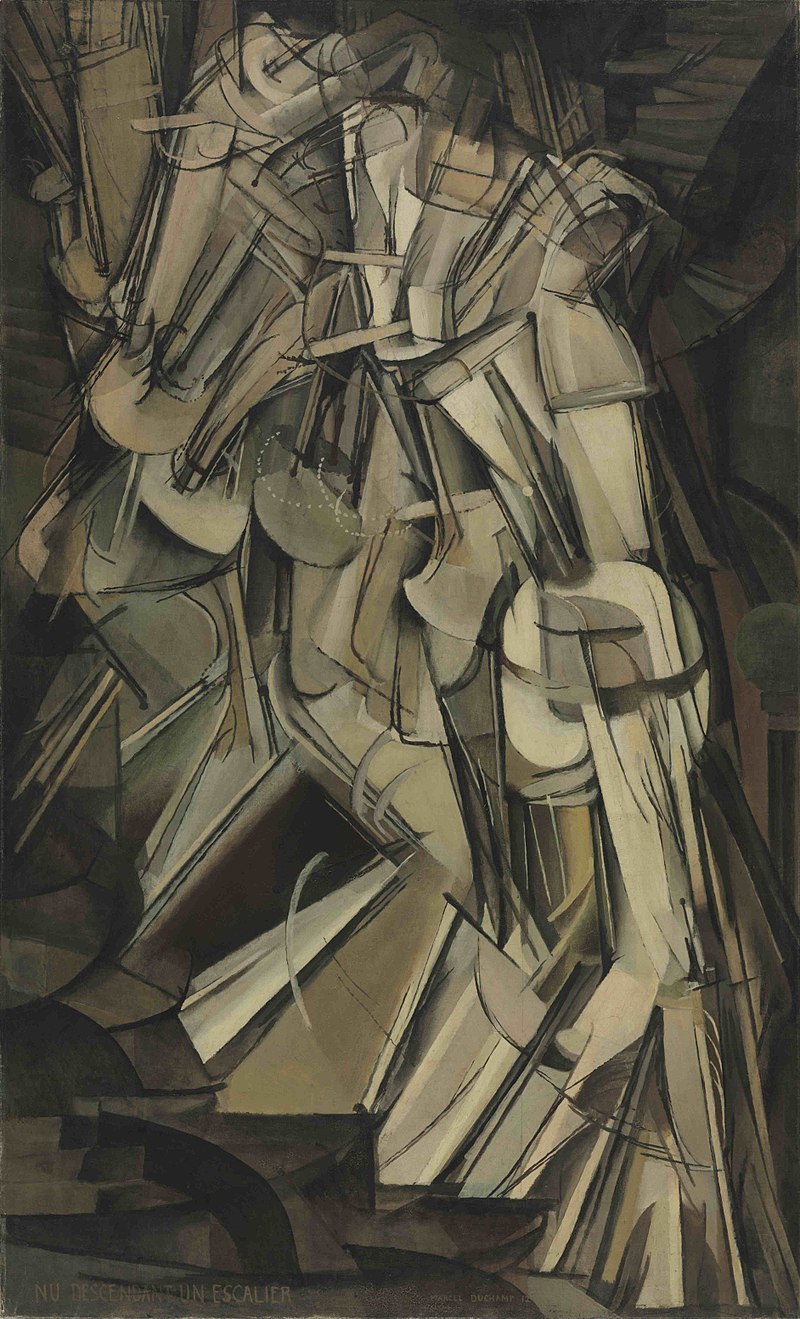

Marcel Duchamp arrived in New York to a hero's welcome, a far cry from the disdainful treatment he was receiving in France. He was hailed for his success at the 1913 Armory Show, where his painting "Nude Descending a Staircase" was the hit of the show.

"Nude Descending a Staircase" was considered radical art, but it was still oil paint on canvas. Duchamp would soon leave even that much tradition behind.

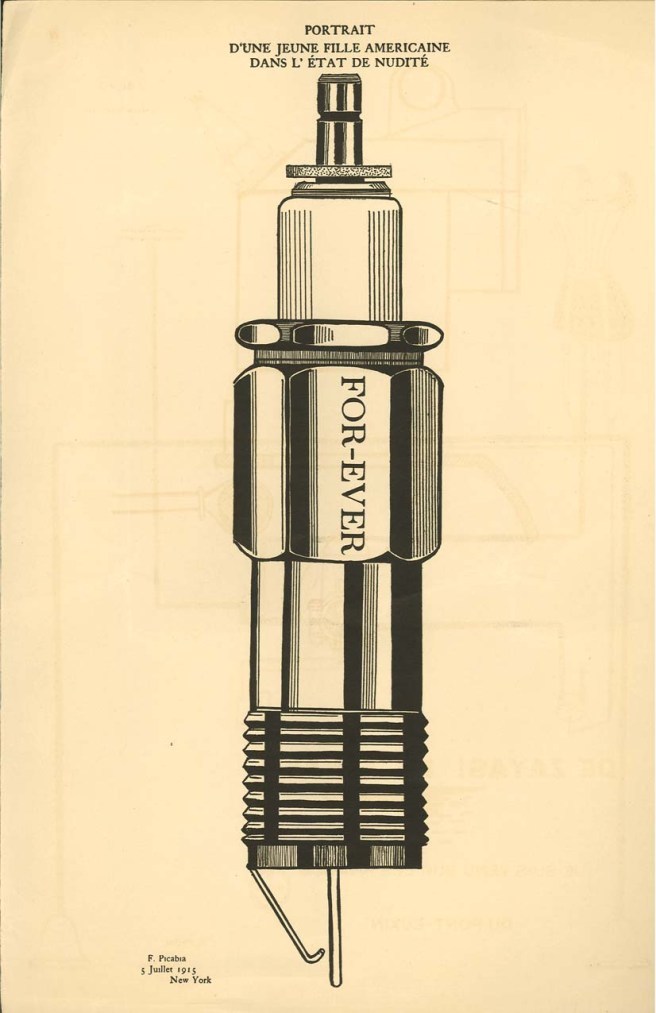

Francis Picabia was handsome, rich, dashing, and about as faithful as an alley cat. That he wasn't court martialed for neglecting his diplomat mission to Cuba for artistic shenanigans in New York was entirely due to his family's wealth and influence. He was also well known in New York for his visit there during the Armory Show.

Picabia abandoned traditional painting for meticulous line drawings of mass-produced items, including this work, titled "Young American Girl in a State of Nudity."

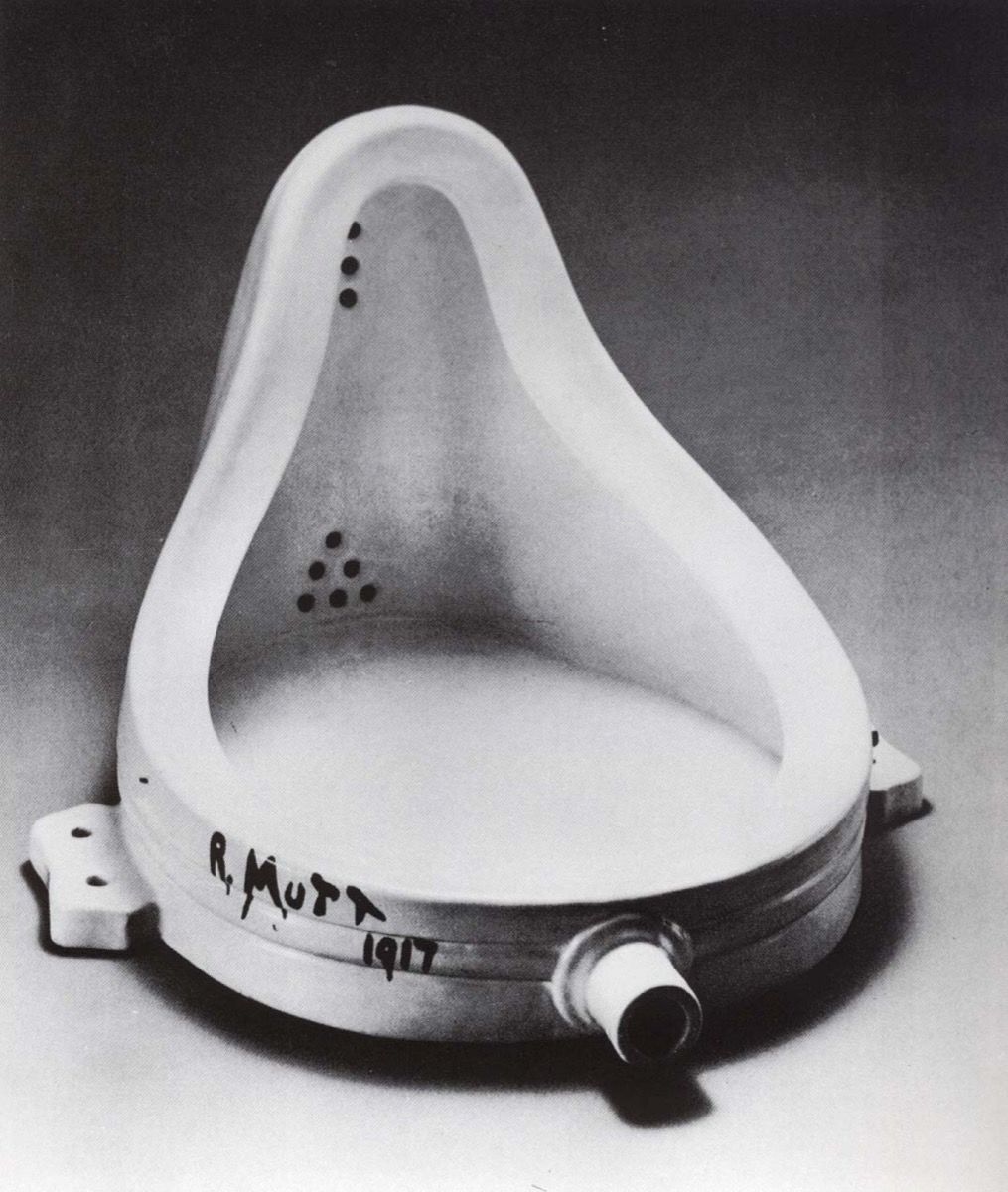

Duchamp horrified New Yorkers when he presented "Fountain" to an art exhibit as a work of sculpture. A urinal may not seem particularly shocking now, but it violated any number of taboos in 1917.

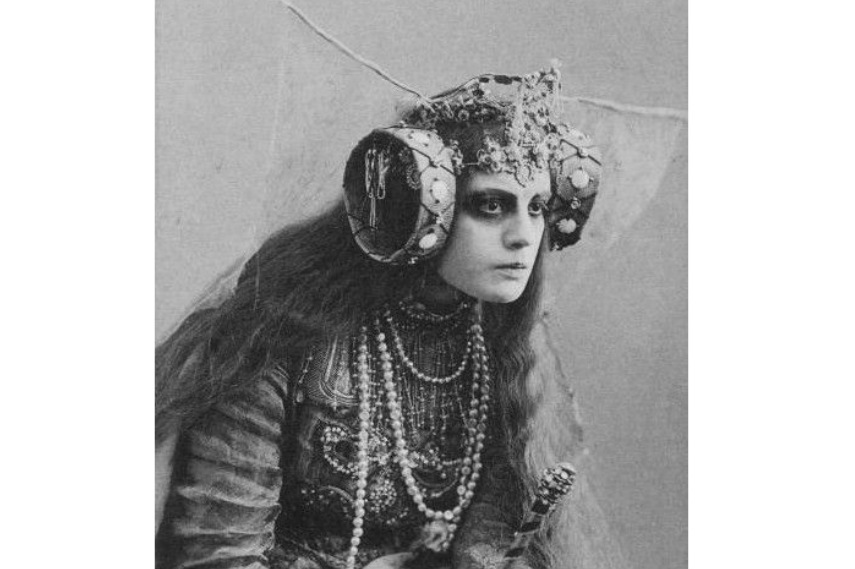

While "Fountain" is generally atttributed to Duchamp, it is possible, although by no mean certain, that it was actually created by the Baroness Else von Freytag-Loringhoven. A German ex-pat, she was creating art out of ready-made objects more than a year before Duchamp and lived her life as a kind of non-stop performance art. Whatever her role in "Fountain," she deserves to be better remembered as a pioneering modernist.

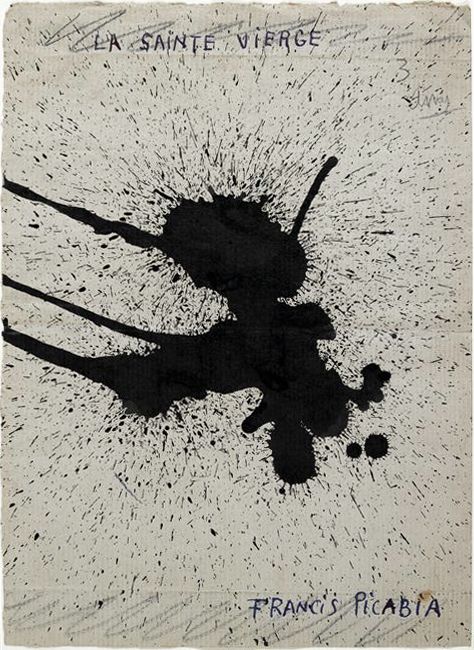

After he returned to Europe, Picabia's art became less disciplined and more outlandish. He titled this ink-blot "The Virgin Saint."

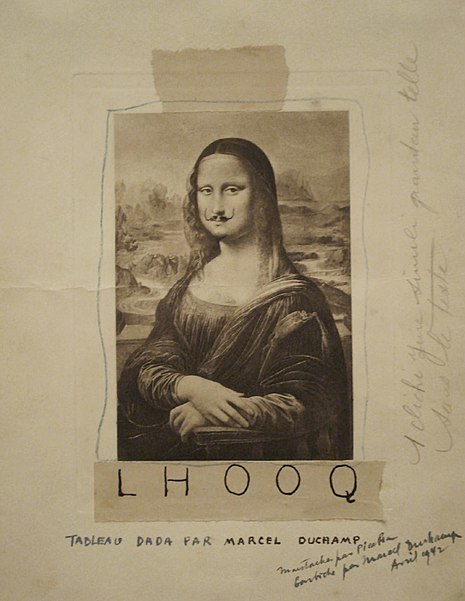

Picabia also published a Dadaist journal, in which he published this work by Duchamp. It's a cheap postcard of the "Mona Lisa" to which he added a mustache. The title "L.H.O.O.Q. is a pun in French; it sounds like "she has a hot ass."

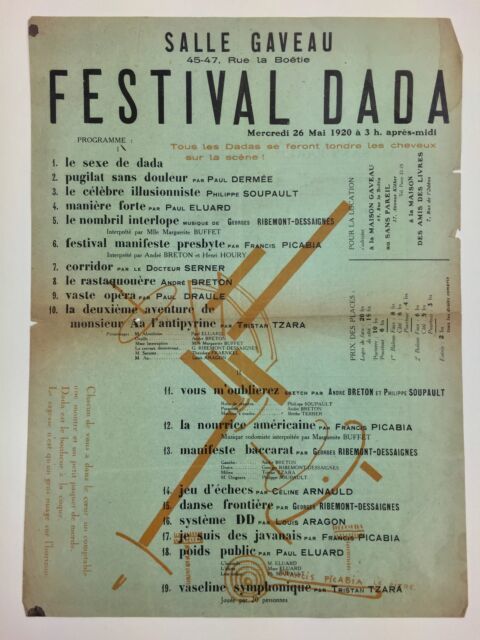

Tzara and other Dadaists in Paris devoted themselves to events and performances. This is a handbill for a "Festival Dada" that took place on May 26, 1920. Tzara and Picabia are listed as performing, along with several other prominent Dadaists including Andre Breton, Louis Aragon, and Paul Eluard. These evenings became increasingly frantic and nihilistic as Dada wore on.

By 1919, Pablo Picasso part of the artistic establishment and no longer a radical on the edges of society.

In 1911/1912, Picasso paintings looked like this--this is "Ma Jolie," a dense, complicated, frankly intimidating Cubist painting.

Ten years later, he painted this work, Woman in White. With its clarity, beauty, and nods to tradition, it is a prime example of Picasso's embrace of neo-classicism after the Great War.

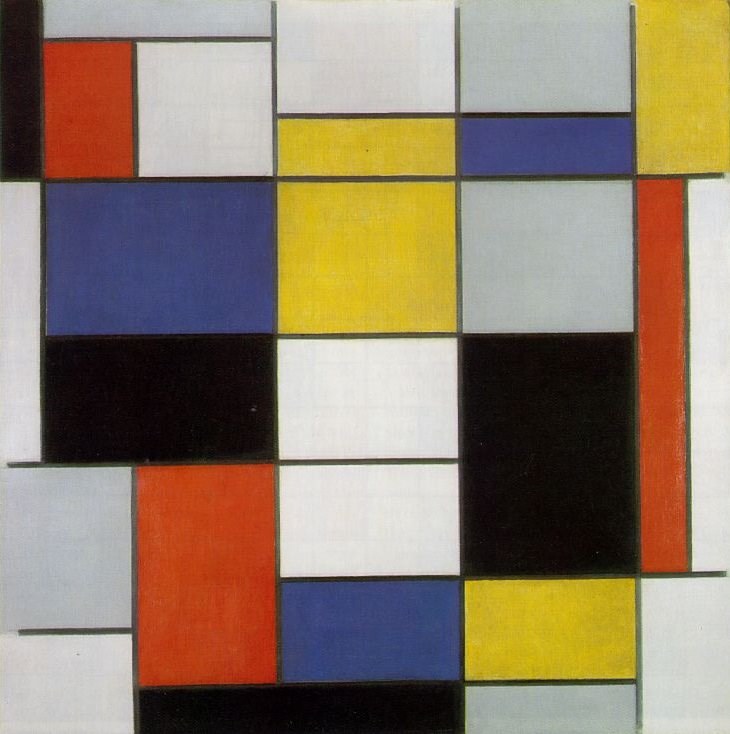

The impulse to create clear, simple, ordered art existed in many European countries. In the Netherlands, Piet Mondrian worked in the Neoplasticist movement creating his iconic grid paintings. This is "Composition No. 2" from 1920.

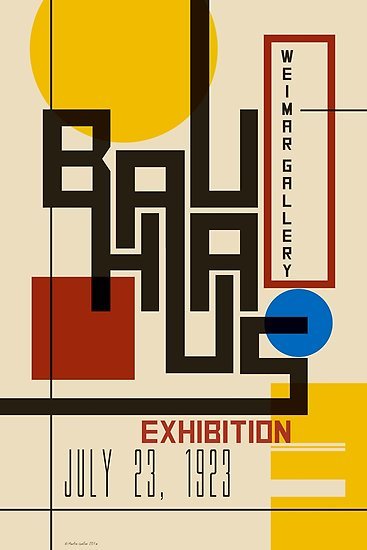

At the same time, in Germany the Bauhaus was established. As a school of arts and crafts, it taught a stripped-down, clean aesthetic that applied to everything from architecture to furniture design, industrial design to graphic design. This poster advertising a 1923 exhibition is a good example of Bauhaus design and typography.

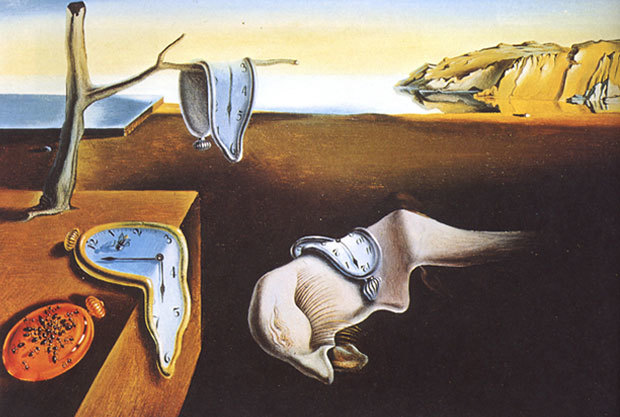

The Surrealist movement arose out of Dada's ashes in the mid- to late-1920s. It combined the traditional painting technique of neo-Classicism with the bizarre imagery of Dada. Salvador Dali's "Persistence of Memory," for example, is a technical masterpiece, with masterful execution. It's also impossible and, frankly, disturbing.

T.S. Eliot's "The Waste Land" gives the impression of randomness, of lines picked out of a coat pocket. In fact, it is painstakingly constructed and shows as much technical skill as Dali's clocks. You can read the poem, or listen to Alec Guinness read it--or maybe do both at the same time.

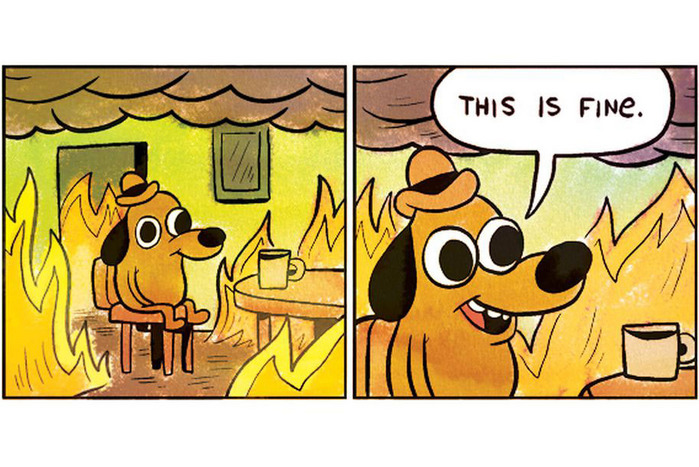

This meme was created in 2013 by cartoonist KC Green. It captures the Dadaist attitude that shows up in popular culture a great deal here in 2019--a sense that the world is really weird right now.

- Please note that the links below to Amazon are affiliate links. That means that, at no extra cost to you, I can earn a commission if you click through and make a purchase. (Here's what, legally, I'm supposed to tell you: I am a participant in the Amazon Services LLC Associates Program, an affiliate advertising program designed to provide a means for me to earn fees by linking to Amazon.com and affiliated sites.) However, I only recommend books that I have used and genuinely highly recommend.

Episode Links

- Destruction Was My Beatrice: Dada and the Unmaking of the Twentieth Century by Jed Rasula — A really well done history of Dada from its origins in Zurich to its collapse in Paris. Rasula's book was my primary source for this episode, and I recommend it very highly.

- Francis Picabia: Our Heads Are Round so Our Thoughts Can Change Direction by Anne Umland, Cathérine Hug, Francis Picabia, George Baker, Carole Boulbes, Masha Chlenova, Briony Fer, Gordon Hughes, Michèle Cone — This is a pricey exhibit catalog, but it's also the best English-language biography of Picabia I've ever found and contains an excellent cross-section of his work.

- Marcel Duchamp: The Bachelor Stripped Bare: A Biography by Alice Goldfarb Marquis — My favorite biography of Duchamp, and I've read several. (Duchamp haunts my career, along with Stravinsky's "Rite of Spring." I can't seem to escape them.) The author looks beyond the mask that Duchamp tried to keep between himself and the world.

- "Biography of Elsa Von Freytag Loringhoven" from Widewalls — A short but compelling biography of the Baroness. I'm not entirely convinced she created "Fountain," but I'm not convinced she didn't either. In any case, she's an important figure who should be better remembered.

- "Cabaret Voltaire: A night out at history's wildest nightclub," by Alastair Sooke BBC Culture — A look at Cabaret Voltaire, where Dada began.

- School of Paris: The Historical Context by Jeanne Willette, Art History Unstuffed — A really good introduction to Return to Order in post-war Paris. Art History Unstuffed is really an excellent resource.

- "This Is Fine creator explains the timelessness of his meme," - The Verge — A fun interview with the creator of the iconic--and very Dada-esque--meme.