Incident at Chelyabinsk: The Russian Revolution and Conflict in Eastern Europe, Part I

September 24th, 2019

47 mins 51 secs

Season 1

Tags

About this Episode

One of the strangest conflicts of the Great War happened 1000 miles east of Moscow between two units of Czech and Hungarian former POWs. What these troops were doing on the edge of Siberia is a fascinating tale of ethnic resentments, self-determination, and unintended consequences.

Notes and Links

A word about dates. Anyone writing about the Russian Revolution must wrestle with the date issue. The Russian empire used a different calendar than the rest of the world for several centuries. This means that the Russian calendar ran about two weeks ahead of the rest of the world. So an event such as the February Revolution occurred on February 23rd on the Russian calendar but March 8 on the western calendar.

The Bolsheviks converted to the western calendar in February 1918, making life easier for them but more complicated for humble podcasters a century later who must decide which date system to use. I have chosen to give dates before the Revolution according to the old calendar, as people in Russian themselves would have experienced them. So in my text, the February Revolution happens in February and the October Revolution in October.

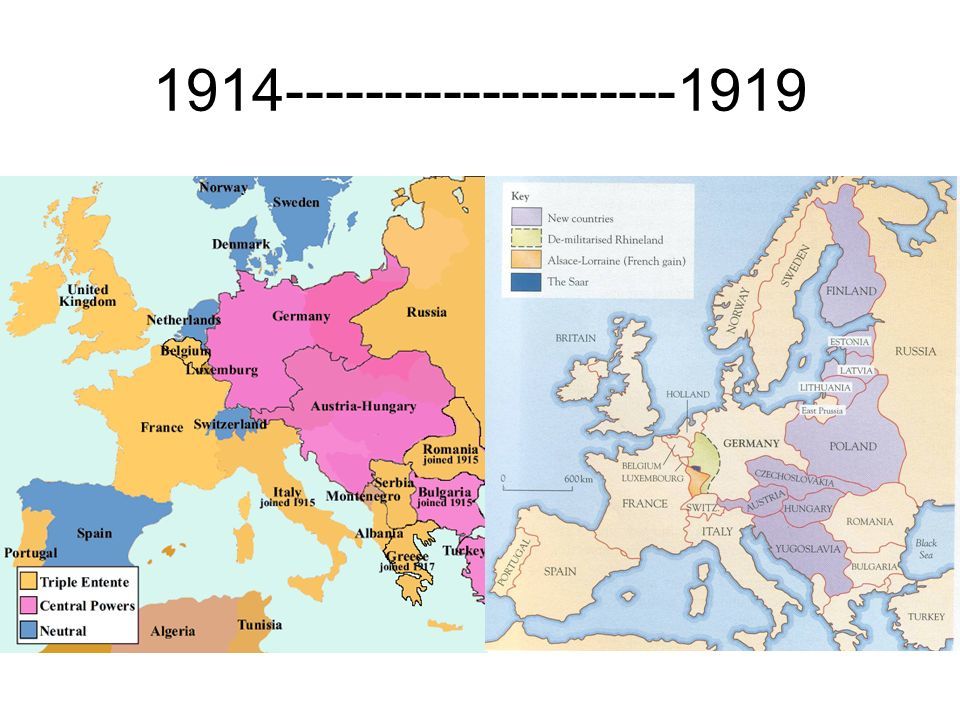

Comparing the map of Europe before and after World War I reveals how many new nations came into being after the collapse of the Austria-Hungarian empire and the division of territory by the Paris Peace Conference. For years the Armistice, armed conflict stretched from southern Finland through the Baltics, Poland, Germany, Czechoslovakia, Austria, Hungary, Yugoslavia, Bulgaria, and Romania.

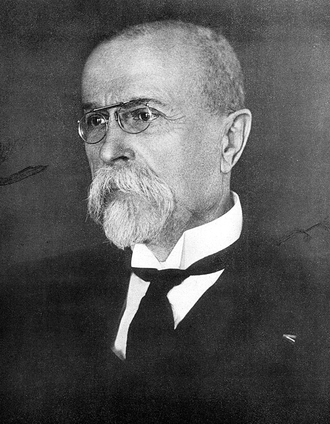

Before the Great War, Tomáš Masaryk was a professor of philosophy and Czechoslovak nationalist leader. He fled Prague early in the war and spent time in London drumming up support for a new Czechoslovak nation. After the Tsarist regime was overthrown in February 1917, he traveled to St. Petersburg to convince revolutionary leaders to allow the creation of a Czechoslovak Legion drawn from POWs that would fight the Central Powers.

Russian POW camps were grim, overcrowded, and disease-ridden. They only became worse after the Revolution, when the new government put little priority on the care and feeding of prisoners. POWs were eager to leave the camps, to go home, to support the Czechoslovak Legion, or to join the Bolsheviks.

Tsar Nicholas II was the heir to the 300-year-old Romanov dynasty and the supreme autocrat of all Russians. In effect, the entire nation was his personal fiefdom. He was diligent and hardworking but utterly unprepared for the task of rule and, frankly, not very smart.

Nicholas was married to Alexandra, a granddaughter of Queen Victoria, and the couple had four daughters and one son. Alexandra became even more passionate about Russian autocracy than her husband, once telling her grandmother than the Russian people love to be whipped.

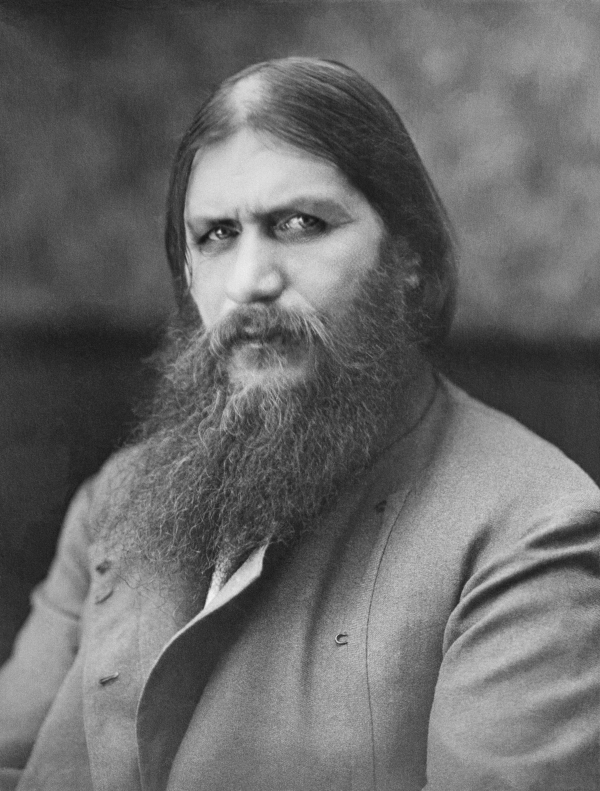

Alexei, the young son and heir, had a blood disease hemophilia. He was frequently ill and likely would not have lived to adulthood. The trauma of her son's illness sent Alexandra scrambling for help and healing. She found both in the peasant mystic Grigori Rasputin.

Rasputin was foul-mouthed, lecherous, and dirty, but he convinced the Empress that he and he alone could save her son.

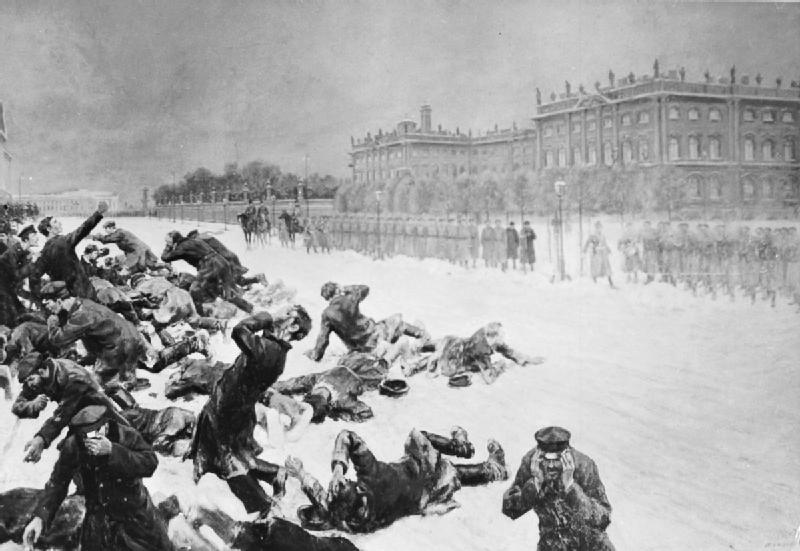

During the 1905 Russian Revolution, the people rose up in protest, but the military remained loyal to the regime and put down riots before they got out of hand. In one incident, troops opened fire on peaceful protesters, killing hundreds; this is an artistic representation of that scene. The Tsar implemented reforms to limit the revolution, but he walked them back as soon as possible.

By 1917, the military had lost faith in the regime and began supporting protesters rather than fighting them.

After the Revolution, the Provisional Goverment tried to control the government. On paper, they looked powerful, but in reality they quickly squandered any authority they might have had.

The soviets or councils of Moscow and Petrograd had the real power in 1917. They were large, unruly bodies made up of factory workers, peasants in from the countryside, soldiers, and a handful of trained, experienced communist organizers. They attempted a form of direct democracy that ended up disorganized and brutal.

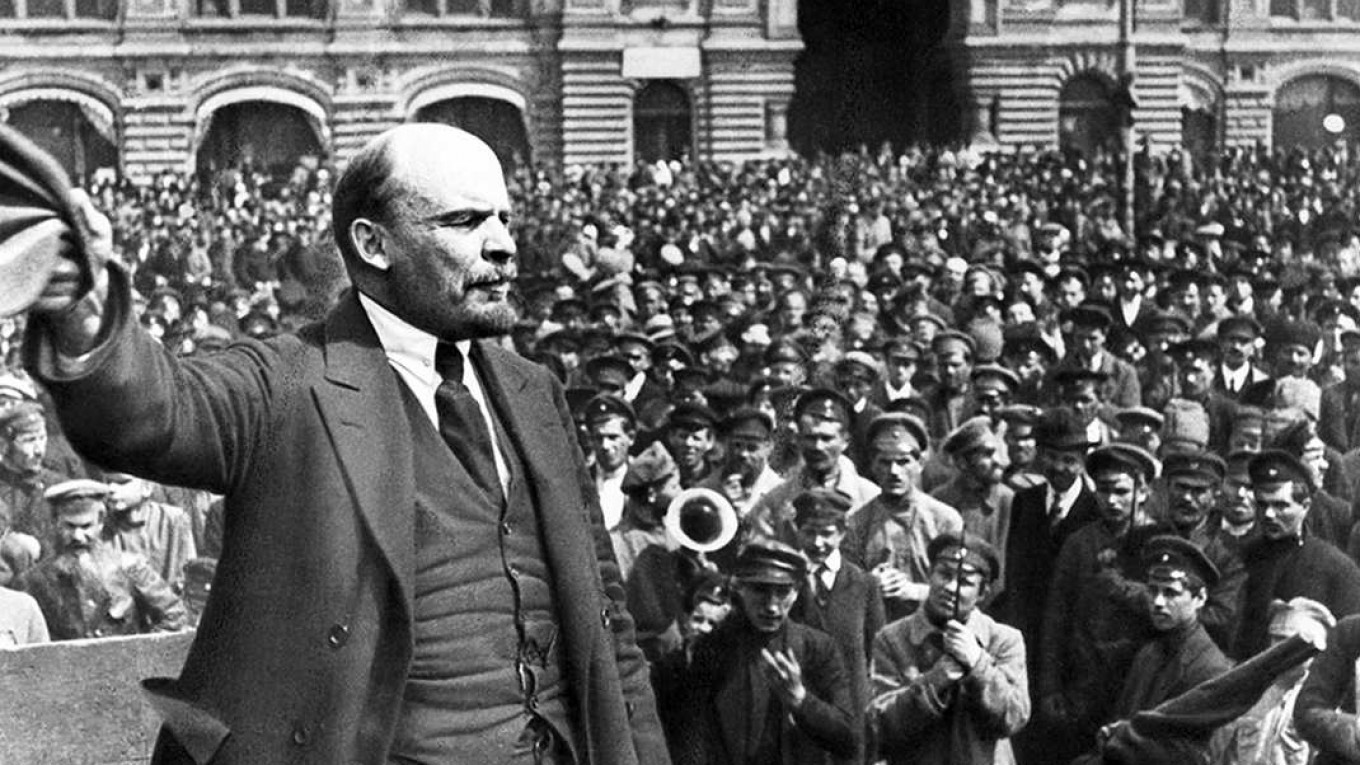

Vladimir Lenin rushed back to Russia after the Revolution and quickly began organizing the Bolsheviks into the most formidable political force in the country. He and his party seized control in October 1917.

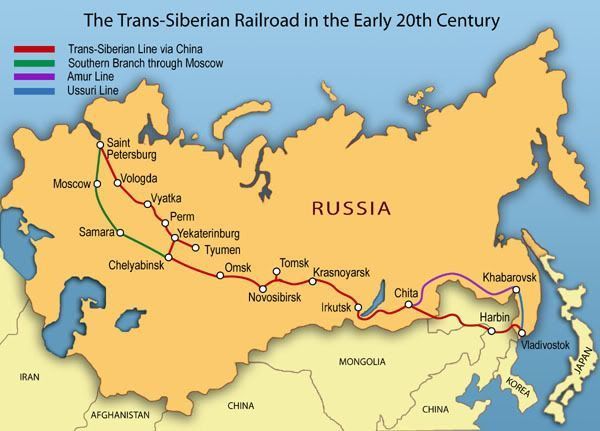

The Czecho-Slovak Legion traveled east along the Trans-Siberian Railway. This map shows the entire route of the railway. The Legion actually joined the railway on a leg not pictured on this map that extended into Ukraine southwest of Moscow. According to their original plan, they would have to travel roughly 5000 miles from Ukraine to Vladivostock.

A unit of the Czechoslovak Legion stands with one of their trains on the Trans-Siberian Railway.

Five members of the Legion pose in a photo studio. I love this photo--it raises so many questions. When and where did they find a photo studio? Who came up with the pose? Did anyone recognize how silly they looked against a clearly painted backdrop of a classical column?

Please note that the links below to Amazon are affiliate links. That means that, at no extra cost to you, I can earn a commission if you click through and make a purchase. (Here's what, legally, I'm supposed to tell you: I am a participant in the Amazon Services LLC Associates Program, an affiliate advertising program designed to provide a means for me to earn fees by linking to Amazon.com and affiliated sites.) However, I only recommend books that I have used and genuinely highly recommend.

Support The Year That WasEpisode Links

- Dreams of a Great Small Nation: The Mutinous Army that Threatened a Revolution, Destroyed an Empire, Founded a Republic, and Remade the Map of Europe by Kevin J McNamara — McNamara's book is one of the few texts available on the Czechoslovak Legion. I found the book incredibly useful in understanding both the motives and the logistics of the Czechslovak nationalist movement and the Legion.

- A People's Tragedy: The Russian Revolution: 1891-1924 by Orlando Figes — There are many excellent books about the Russian Revolution, but I found Figes' to be the most helpful. This is not a casual book, and it will require sustained attention, but it never loses focus on the human scope of the Revolution.

- The Romanovs: 1613-1918 by Simon Sebag Montefiore — This is a really fascinating look at the entire history of the Romanovs, and it opened up a lot of history to me. It also paints a picture of the slow accumulation of missteps, errors in judgment, and, sometimes, utter idiocy that paved the way to revolution.

- Nicholas and Alexandra: The Classic Account of the Fall of the Romanov Dynasty by Robert K. Massie — Massie's book was published all the way back in 1967, and I must have read it for the first time about 1980. It was published in one of those Reader's Digest condensed books that everyone's grandparents (including mine) seemed to have. Would I rely on it exclusively for an academic paper? No, but it's still a good read and an insightful psychological study of the emperor and empress.

- Fighting Without A Country - Czechoslovak Legions of World War 1 -- THE GREAT WAR Special - YouTube — I've praised The Great War series on YouTube more than once, and I must do so again. They provide a great summary of the adventures of the Czechoslovak Legion.

- Revolutions — Mike Duncan's always amazing "Revolutions" podcast began its examination of the Russian Revolution, and of course it's fantastic. He is spending weeks on events I skip over in a sentence, so if you want to dive deep, make sure you're listening.